Chevron and The Hawaiian Judge Dominant Strategy

The purpose of a law is what it does. What it does, is what the judge says it does.

The Chevron doctrine has been overturned by the Supreme Court. It’s a blow to regulators, because Chevron basically said they could interpret somewhat vague laws how they saw fit, and then apply what they believe it should mean. The conflict of interest is apparent. In a country mostly ruled by unelected bureaucrats, it’s positive to have it gone.

Chevron U.S.A., Inc. v. Natural Resources Defense Council, Inc., 467 U.S. 837 (1984), was a landmark decision of the United States Supreme Court that set forth the legal test used when U.S. federal courts must defer to a government agency's interpretation of a law or statute.[1] The decision articulated a doctrine known as "Chevron deference".[2] Chevron deference consisted of a two-part test that was deferential to government agencies: first, whether Congress has spoken directly to the precise issue at question, and second, "whether the agency's answer is based on a permissible construction of the statute".

Overturning Chevron is good in that it detracts from regulatory power and makes adjudicating these disputes less of a kangaroo court. But power is a zero-sum game, where did it just redirect to? It just rerouted to another set of unelected bureaucrats: the judiciary.

Even more authority has now been handed to judges. Judges are effectively despots, who can do nearly whatever they want in that small room where they're basically kings. The interpretation of the law is what they say it is when you’re in their courtroom. The same conflict can have two completely different rulings depending on who's wearing the robes that day.

The judge's politics guide the interpretation of laws; this is part of the human condition. You can try to suppress it, but you cannot eliminate it. It doesn't matter where you went to school or what legal doctrines you espouse; because those legal doctrines are actually moral beliefs, manifesting as law philosophy.

Your moral foundations will always be expressed in interpretive political analysis; because your political beliefs are simply your moral beliefs. And if it's legally subjective, it's inherently political. No matter what the judge says or how many oaths she signs, her moral convictions are seeping through into her decisions.

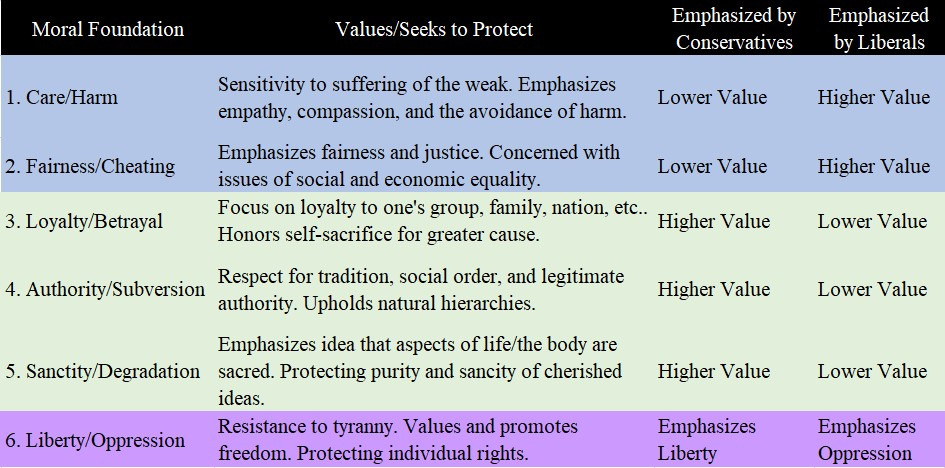

Here are the six moral foundations, covered in a previous essay Yarvin, Rufo, and Endless Factual Sediment.

The following are the legal doctrines of a “conservative” judge vs a “liberal” one, stripped down to their core principles and motivations:

Originalism (conservative jurists): is the legal philosophy of the authority/subversion moral foundation. You defer and adhere to the authority of those who made the law based on their intentions, not yours, when applying it. This should occasionally produce rulings you personally find to be unjust, even abhorrent. But that’s how it is sometimes, because your duty is to apply the law as written and intended, not give your political opinions. You don’t like it? Persuade your fellow man to change the rules: legislators legislate, judges apply legislation.

"The Living Constitution", aka Progressivism (liberal jurists): is the legal doctrine of fairness/cheating and care/harm. Applied law is whatever you think is fair, wrapped in comforting phrasing such as legislation being “dynamic” and “serving modern society”. What’s “dynamic” and “modern” has little if any consideration for the law as originally written, because you’re expressing moral tenets with post-hoc legal rationale. This is what “legislating from the bench” means.

As a result, you probably personally agree with most of your rulings when this is your north star. It's a very enticing form of legal philosophy for this reason: it’s quite empowering and satisfying to always morally endorse your rulings.

A sign of a good jurist is hating some of your decisions on a personal level. Scalia taught me this. You should have antipathy for some of your rulings, because following the law should not always be rewarding and align with your worldview.

Law is the language of order, and imposing order is sometimes unpleasant. A “living constitutionalist” experiences no such unpleasantness, because the doctrine that guides their judicial worldview will almost always produce an outcome that they personally support. That is not what the practice of law looks like, and it’s becoming increasingly common, as apparent by the hyperpoliticization of the court-appointee process.

A reminder of how far the SCOTUS process has fallen: Scalia was appointed by a vote of 98-0. There’s basically zero chance he’d get confirmed today with anything less than 51 Republican seats in the Senate. That’s what electing a good jurist looks like, not your best friend who has the same opinions as you.

Spoken from the man himself:

Originalism (guided by Textualism) is the only genuine attempt at legal analysis, because it best endeavors to separate the judges feelings from what the law dictates. It’s imperfect, but it’s the cleanest shirt we have in the dirty hamper. Everything else is legislating from the bench, because it’s transparently an unalloyed derivative of the judge’s political opinions; this kind of thinking is becoming more en vogue and ostentatiously adopted.

Why The Judge Matters

Judiciary power is vast, and its application is deeply interpretative. In an increasingly politicized environment, this unavoidable subjectivity will be exploited. It's why you see judge shopping, and why you’ll likely see more of it as the legal system comes under further political pressure.

Remember when that obscure judge in Hawaii blocked Trump's immigration orders while in office, and then kept doing it. A policy the president campaigned on and was democratically elected to implement, but one little tyrant said "no, I don't see it that way."

Why'd they take the case to Hawaii? Is it because the law is better understood by the beach? Or because they knew a liberal judge would give them the ruling they wanted if they said "Aloha"?

With Chevron gone, state overreach will recalibrate towards a new path. I'm fearful more judge shopping will happen as a means for them to still get what they want. Because even more power has now been handed to an overtly politicized legal system: The Hawaiian Judge dominant strategy?

Judges matter, a lot. The only reason I care about the presidency is because of the judicial appointees he gets to make; because the judiciary exerts actual power over the people and lasts well beyond four years. The president is otherwise mostly a totem; a figurehead that speaks loudly but carries a rather small stick. The unelected bureaucracy of government workers that run the institutions that run much of our lives cannot be fired or controlled by him. When people say “Deep State”, this is what they’re referring to.

In future essays, I’ll break down how these moral foundations are biologically ingrained manifestations of your temperament, what I call Biofoundationalism.

And just to be clear, I think the Chevron overruling is absolutely a positive event and I’m glad it’s gone. This is reflecting on how regulatory strategy recalibrates and the philosophical frameworks behind judge decision making.

Related essays:

We'll Give You Things > We'll Leave You Alone

Elon, Yarvin, and Verbal vs Embodied Understandings

Follow @BackTheBunny

I am curious as to your views on Biofoundationalism. I am not familiar with the concept, but going by your definition—“your views are (at least partially) determined by your temperament” I find it to sync rather well with the way I see the world. Different people with different temperaments can understand the proper motivations of law entirely differently, and when you dig down into why they believe the way they do… One often finds irreconcilable differences between them. Intelligent minds can disagree, after all.

Good news is that the court opinions are plastic, and change with the seasons. Reading the top 100 Supreme Court cases made me realize the judges have always been making up the law as they go along.

But judges have more accountability than the bureaucrats, and different incentive structures.